NOTE: Carolyn Curlee Robbins, currently the Curator of Education for the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (http://www.smoca.org/) in Scottsdale, Arizona, wrote her Master’s Thesis comparing the hardrock miner paintings of William D. White with those of Arizona native artist, Lew Davis, a contemporary of White’s. The excerpt presented below is copyrighted material and may not be used or reproduced in any form without express written permission from the author.

In the early 1920s, William Davidson White traveled from his home on the East Coast to the remote yet bustling mining communities in southern Arizona and northern Mexico to fulfill a commission to paint images of the miners employed by the Phelps Dodge Corporation.(1) Little has been discovered about the life and career of this artist from Wilmington, Delaware, yet his legacy is apparent in Arizona, for twenty-three of his paintings of the copper miners are still located in the state.(2)

Before coming to Arizona, however, White received artistic training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied with Emil Carlson and Cecilia Beaux, among others, from 1914 to 1916.(3) During the economically disastrous years of the 1930s, White found employment with the Works Progress Administration in Delaware, which classified him as a “senior artist, grade 1.”(4)

In April 1934, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C., mounted the National Exhibition of Art by the Public Works of Art Project. Among the objects included in that exhibition was a print by William Davidson White entitled 0ld Stone Barn.(5) White also executed easel paintings and drawings for the PWAP, including three paintings of Civil Works Administration workmen. White considered Harvest, Spring and Summer (1937), a five-panel mural executed for the Dover, Delaware, Post Office under the Treasury Relief Art Project, to be his finest work. The Smithsonian American Museum of Art owns two oil studies for this mural.(6) (More about this Mural may be found under Biography.)

Throughout his career, White displayed an interest in the working man as subject matter. Moreover, the miner became a favored theme, for he accepted a job with a company in Pennsylvania to paint the miners in their anthracite coal fields, where he returned many times, and that commission led to other work for mining and engineering companies around the country. White once commented that “the drama of [the miners] lives and of the country greatly impressed” him.(7)

White’s illustrative approach to art appealed to his patron, P. G. Beckett, General Manager for western operations of the Phelps Dodge Corporation. Beckett was enamored of his profession, fond of his adopted state of Arizona, and proud of the achievements of his employer. His pride is understandable, for “during the years Percy Gordon Beckett ran Phelps Dodge Corporation’s Western Division, the company acquired the additional resource base that allowed it to develop into the nation’s second largest copper producer.”(8) In a desire to adorn his home in Douglas, Arizona, and later his office, with images of the Phelps Dodge miners, he commissioned the Delaware painter, W. D. White, to execute a number of paintings.

Around 1921, White made the long journey westward, where he toured the Phelps Dodge copper mines in Arizona and northern Mexico, made photographs, and then returned to his studio in the East to execute the paintings. To facilitate Beckett’s selection, White sent photographic illustrations of the pictures to Beckett in Douglas.(9) Beckett selected a number of the oil paintings, seventeen of which form the Beckett Collection of paintings by White. In 1958, he gave the paintings, along with a mineral collection, to the College of Mines at the University of Arizona in Tucson.(10)

Sometime during the mid-1930s, W. D. White was again asked by a Phelps Dodge official to execute paintings of the Arizona miners.(11) The official, Louis Shattuck Cates (1881-1959), became President of the Phelps Dodge Corporation in 1930 and maintained his headquarters in New York City, but frequently returned to Arizona to inspect the properties of his mining company.(12) Six paintings by White, which evidence indicates are those commissioned by Cates, now belong to the Jerome Historical Society and are housed in the Mine Museum in Jerome.(13)

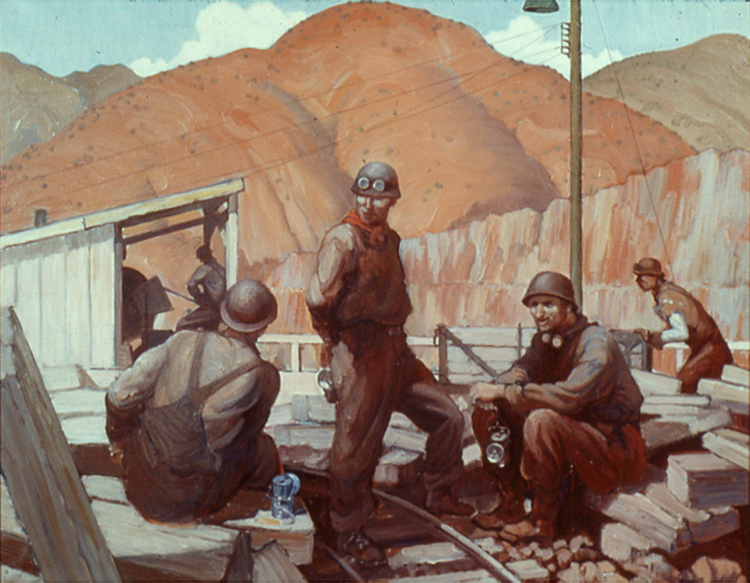

The well-balanced composition of White’s Shift Change (c. 1935-7, Cates Collection, pictured below) is typical of a formula used by him. His large, competently rendered, self-assured miners, centrally placed on the picture plane, immediately capture the viewer’s attention. Fellow workers energetically perform their tasks in the middle ground, and the background reveals a panoramic desert landscape and part of an enormous open pit mine. The earth-toned pigment is applied boldly in a thick impasto, suggesting the use of a palette knife. The natural light source, which falls from the left rather high in the sky, casts deep shadows. The three miners in the foreground stand or sit erectly and smile pleasantly. Here the miner is heroic in service to the company and to the system.

Another underground scene, Driller (c. 1937, Cates Collection, pictured below), depicts a miner using a pneumatic drill, run by compressed air and cooled by water drawn from a tank through hoses which snake about the floor of the small chamber and loop up to the drill. The driller, traditionally the elite and usually of Welsh or Cornish descent, is self-possessed, strong, heroic and proud of his occupation. The determination on his face and deliberateness and alertness of his posture evoke the image of a soldier stationed at the battle front, ready to fire his weapon in defense of his country. Evocation of such a mental image surely appealed to White’s industrial patrons, for clearly the miner is heroic in service to the company, as a soldier is heroic in service to his country. White emphasized the importance of the miner and his task through formal means by posing him centrally in the composition and brightly highlighting the glowing face of the stope toward which the drill is aimed.

Although White’s style is not innovative, he is a technically competent painter who satisfactorily fulfilled his obligations to his patrons. No deep meaning or symbolism is expressed in White’s paintings. He does not address vital social or political issues, such as economic depredation, danger on the job, racial and job discrimination, anti-union sentiment of company officials, or the miners’ lack of control over their own lives. Instead, White communicates, through an optimistic and industrious demeanor, the heroism of the miner in service to the company and to the system, that results in the prosperity and success of the Phelps Dodge Corporation during this period.

NOTES:

1. W. D. White, letter to Jerome Historical Society, 18 July 1955.

2. Seventeen paintings are located in the Mineral Museum, Geosciences Department, University of Arizona, Tucson, and six at the Mine Museum, Jerome Historical Society, Jerome, Arizona.

3. Virginia Mecklenburg, The Public as Patron (College Park: University of Maryland, 1979) 114; and Marietta P. Bushnell, Librarian, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, letter to author, 7 May 1986.

4. Jeanette Eckman Papers, WPA – Delaware, Archives of American Art, Microfilm Roll NDA 15.

5. See National Exhibition of Art by the Public Works of Art Project, Exhibition catalogue Washington: The Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1934), Davis, Store for Rent, #226; White, Old Stone Barn, #346.

6. Mecklenburg 114. The building in which the mural is located is now the Educational Building of the Wesley United Methodist Church, Dover, Delaware. See Marlene Park and Gerald Markowitz, Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984) 205.

7. Mecklenburg 114.

8. Phelps Dodge, a Copper Centennial, 1881-1981, Supplement to Arizona Pay Dirt (Summer 1981) 148. Beckett (b. 1882, Quebec; d. 1973, Arizona), who had a long and distinguished career in mining, was General Manager of the western Division of the Phelps Dodge Corporation from 1920-1924, Vice-President and General Manager from 1924-1937, then Vice-President from 1937 until his retirement in 1946.

9. John H. Davis, Jr., retired mechanical engineer for Phelps Dodge Corporation, of Douglas, personal interview, 26 July 1986. Davis’s father, John Davis, Sr., was an assistant to Beckett, and the Davis family lived in company housing next door to Beckett’s home in Douglas.

10. Arizona Wildcat, 28 Jan. 1958, 2; and “Gifts and Loans,” College of Mines Newsletter, University of Arizona, Tucson (Fall 1959).

11. W. D. White, letter to Jerome Historical Society, 28 July 1955.

12. In 1915 Cates was general manager of the Consolidated Copper Company in Ray, Arizona.

13. The provenance of these paintings is rather obscure. For a number of years residents of Jerome have believed that Lewis Douglas, owner of the United Verde Extension mine in Jerome, owned the paintings, hung them in his home in Jerome, and gave them to the American Legion Post in Jerome in the early 1920s. Some years later the paintings supposedly were moved into the Phelps Dodge Club House. See Secretary-Treasurer of the Jerome Historical Society, letter to W. D. White, 2 Aug. 1955. This supposition, however, seems to be completely erroneous. According to White’s letter of July 28, 1955 to the Jerome Historical Society, the commission for the second set of paintings came from Cates seven years after the Beckett commission. No mention is made of Lewis Douglas nor his father, previous owner of the United Verde Extension. Moreover, John McMillan, a former mayor of Jerome and the Phelps Dodge representative in Jerome after the mine closed, recalls that Cates and Phelps Dodge gave the paintings to the Historical Society around 1953 when Phelps Dodge’s United Verde mine closed. The Mine Museum was actually formed around these six paintings. In all likelihood, Cates commissioned the paintings and hung them in the Phelps Dodge Club House, a facility maintained in Jerome for management personnel of the United Verde Mine, after 1935 when Phelps Dodge purchased the mine, then gave them to the Historical Society when the mine closed for good in 1953.

Evidence indicates that execution of the undated Cates paintings must have taken place around 1937. The pictures in the Beckett collection are dated 1923 and 1924; according to White’s letter of 1955, a commission date of seven years later would fix a date of c. 1930 for the Cates paintings. As Cates only became President of Phelps Dodge in 1930, it would be logical to date the pictures a few years later. Moreover, Jack Davis, who examined photographs of the Jerome paintings, believes some of them depict the Phelps Dodge operation of the open pit mine at Jerome, which was not worked, until 1937. It would appear that with the passage of time, White simply did not recall exactly when the second commission took place.

In addition, characteristics of the Cates paintings indicate they were executed a number of years later than those belonging to Beckett. The palette is consistent throughout the six Jerome paintings. The miners wear similar uniform-like clothing which is in good condition, and possess hard hats, instead of the earlier soft felt ones, and goggles, clearly a later development in promotion of better safety.

Although no evidence has been discovered which verifies White’s return to Arizona after Cate’s arrival in 1930, that possibility should not be dismissed. Two of the Cates paintings appear to be updates of his earlier work for Beckett. Driller (c. 1937) and Mexican Town (c. 1937) are almost identical in composition to Driller (c. 1924) and No. 10 Mexican Town (1924). The only substantial difference is the facial structure of the miners, their dress and the addition of safety equipment. The other four paintings are entirely new imagery. It is possible, of course, that White worked from photographs sent to him by Cates for the second set of pictures. Presumably, Cates saw the Beckett paintings in Douglas sometime after his employment as President of the Phelps Dodge Corporation in 1930 and made contact with White through Beckett.

NC Willis

20 Mar 2012The painting you have is definitely by William D. White, and was undoubtedly done for publication, although I have not yet found the source. Thanks for sharing.

shawna kelly

21 Sep 2011DID W.D.WHITE PAINT A MEXICAN REVOLUTIONARY SCENE IN BLACK AND WHITE.IT COULD PERHAPS BE THE ALAMO. PLEASE REPLY